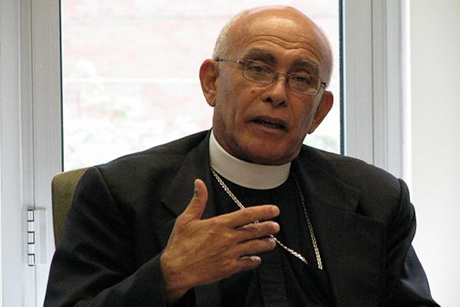

Photo Credit: ENS

Despite the suspension of some activities because of the political chaos, demonstrations, marches, violence and food shortages, priests in the Diocese of Venezuela are getting on with their everyday pastoral work.

The Church has decided to stay out of politics and engage in direct work in communities, as the Diocesan Treasurer, the Rev. Jose Francisco Salazar explains:

“We try to support everything that is beneficial to the community while respecting all ideologies of the people,” he says. “We have tried, as far as possible, not to get involved in political matters, but to help and respect the dignity of human beings. That has been our north. And Bishop Orlando has been very clear on this.”

Recent economic and political measures have led to a shortage of basic foods and medicines. The International Monetary Fund forecasts that inflation in Venezuela will reach 720% this year and, unless things improve, could reach 2.200% by 2017. The New York Times reported last month that the lack of basic medicines and water shortages in some public hospitals, meant operating theatres were not being cleaned after surgery.

To fulfil its social mission and promote mutual help in communities, Episcopal parishes have organised a support network to locate basic food and medicine. Parishioners take turns to go to supermarkets and pharmacies and then communicate what necessities are available in each area. In churches, people write down what medicine they need, information is then shared on the network and then, if the medicine is found, it is bought – even if that is in another city.

“The Church is trying not to lose its prophetic role and is avoiding falling into politics,” says Rev. Salazar. “We prefer that people feel that their priests are with them, they are not the elite who live outside but they live among them and suffer as they do.”

His statement is reflected in the story of Bishop Orlando Guerrero himself, who suffers from diabetes and, like all parishioners, gets his medicine through the network of parishes.

In April the Venezuelan government reduced the working week to three days for public employees and four for private workers. In response, when someone in the congregation is not working, they now offer their day for this work in the parish.

The Church tries to respond to the reality of the country, the Rev. Salazar says, “We have had to mediate in some cases; in others, we counsel families of victims of abuse and violence. Sundays are generally respected. There are almost no protests, and so services are offered on a regular basis. ”

Adapted from The Anglican Communion News Service